I’ve decided to mark my dramatic return to the blogosphere with a couple of election analyses for both the European Parliament election and the UK local elections (coming in a later post) held in the last week. The media in Britain has been awash with stories about a political ‘earthquake’ that has seen the emergence of a four-party system with the rise of UKIP. Yet, from the way it’s being reported, you would think that the entire European project has been brought to its knees. This is not the case. The media, particularly the BBC, has failed to adequately report the Europe-wide picture beyond picking select examples of countries which have seen a dramatic rise in Euroscepticism. There has been a growth in Eurosceptic feeling across Europe but, to be clear, the countries which have seen UKIP-style breakthroughs are in the minority. I’m far from an expert in European politics but I will try to present the general picture as the dust settles across Europe and fill in the gaps that the mainstream media has missed. I will also aim to take a balanced look at UKIP’s electoral victory and argue that why the results show that the major British parties would be wrong to seek to ‘out-UKIP UKIP’ on issues regarding Europe and immigration.

I’ll analyse the results from a progressively larger scale, beginning with Scotland and Wales, passing through the UK and ending at the European Parliament itself.

Scotland

The European Parliament election in Scotland has inevitably been analysed through the prism of the upcoming referendum on independence, it being the last electoral test for the political parties before September. It would be inaccurate to pin the ruling Scottish National Party (SNP)’s electoral fortunes to support for a Yes vote, given that many SNP voters do not favour independence while several supporters of independence come from other parties. Furthermore, the turnout of 33.5% is well below the approximately 80% expected for the referendum. More accurate would be to view the election as a test of the SNP’s popularity after seven years in power. Here are the results:

From a result like this it is difficult at first glance to ascertain which party has ‘won’. If we’re going simply by vote share then it proves to be yet another instance of the SNP topping the polls, yet I doubt that’s how senior strategists shall be interpreting it. Since the Liberal Democrats entered into a coalition with the Conservatives in 2010, the SNP have consistently been taking significant shares of the vote from the Liberal Democrats in both elections and the polls, but that hasn’t happened here. Where did the Lib Dem vote go? You could argue that it’s gone to UKIP, however notice also the 7.04% lost by the ‘others’ – which in 2009 were primarily composed of anti-EU parties like No2EU, or the more extreme British National Party. I’d imagine this would account for around half the UKIP vote. Therefore the unavoidable truth arises that the former Lib Dem vote seems to have gone to Labour rather than the SNP. That said, there is the not insignificant counterargument that the SNP has managed to remain in the top position of what is traditionally an anti-establishment election seven years into power. This is a record neither Labour nor the Conservatives in the rest of the UK can claim within the last twenty years, nor most governments in Europe (Angela Merkel springs to mind as one of the other few exceptions). The result may have been disappointing for the SNP, especially as polls suggested they might attain the mid 30%s, but it’s far from disastrous.

Perhaps a slightly more clear cut image emerges if we look at seats won. The only change here is that the Liberal Democrats lost their only seat to UKIP, who saw David Coburn elected as not only their first MEP in Scotland but their first representative anywhere. Both the SNP and the Greens had been hoping to snap up this third seat, and the fact it’s ended up going to UKIP – a party opposed to many of the SNP’s and Green’s values – will be a disappointment to both. The Scottish Greens can take small consolation that their vote has increased for the four European election in a row, with 8.06% providing them their highest result ever in a national election. We must also not overstate the scale of UKIP’s victory in Scotland. Not only did UKIP receive the lowest vote share in Scotland of any of the UK’s electoral ‘regions’, but also the lowest growth of their vote share anywhere in the UK. Given the national context, the big shock isn’t that UKIP finally broke into Scotland but actually that they still only managed to achieve fourth place. Scotland is no longer immune to UKIP but it still remains well behind the rest of the UK in its support of the party.

In terms of the wider implications, it’s interesting to look at how these results might reflect Scotland’s views towards Europe – if we are to assume that the election results can tell us anything this detailed, of course. 70% of Scottish voters voted for pro-European parties (which can rise to 77% if we evenly split the Tories into pro-Europe and Eurosceptic positions). This contrasts with the UK as a whole where the figure is only around 43%. This will be welcome to supporters of independence, who can use these figures to argue that Scotland is less Eurosceptic than the rest of the country and that there is less demand here for a renegotiated relationship. A less welcome figure would be the fact that the pro-independence parties, the SNP and the Greens, only achieved 37% of the vote between them, though in an election dominated by debate over the country’s place in Europe rather than independence it’s hard to view these results as any reliable indicator of voting intention come September, especially given the low turnout.

Wales

Wales is a very small ‘region’ for the European Parliament, electing only 4 MEPs. If the four main parties manage to achieve very roughly similar levels of the vote then they will all gain a seat and, because of the way the system works (it’s fairly simple – you can see a guide here) there’s quite a large margin of votes which would produce the same result. This is what we saw happen in this election.

As you can see, despite there being a rather dramatic trend to UKIP and a less so but still significant trend to Labour, the seat distribution is unchanged. This does betray one problem of the European electoral system: the D’Hondt system of electing MEPs, although marginally favouring larger parties, will generally give a proportional seat distribution; however when there’s only four seats to distribute it’s impossible to do so in a way that’s completely fair. The regional system the UK uses is essential in ensuring that parties which don’t contest ever seat get represented, otherwise Plaid Cymru would win no seats, the SNP be severely unrepresented while the national parties would be over-repesented. I can’t see a solution to this other than increase the number of seats for each country – which would make the European Parliament a complete mess – but this should be kept in mind. This will be a welcome result for Labour, which suffered a terrible defeat in its traditional stronghold in 2009, though it’s still failed to make up all the ground lost. It’s more bad news for the Liberal Democrats, who have gone from being an already minor force in Wales to virtual wipe-out. The result also confirms UKIP’s position as a major party in Wales. UKIP has grown in Wales during the last decade but it’s always been a step behind the rest of the country, whereas now their vote share is almost directly in line with the national average. But perhaps the greatest relief is for Plaid Cymru, which managed to hold onto the seat by the skin of their teeth after numerous polls suggested they’d lose it to Labour. Nevertheless, this result is more evidence that Plaid Cymru is failing to tap into discontent with the major parties in the way the SNP has achieved up in Scotland.

If we then take our European lens to this result, we see that 51.9% of Welsh voters voted for pro-European parties (around 60% once the Conservatives are split) – not as high as in Scotland, but still above the national average of 43% and a clear majority. Once more, this fact brings to light the limitations of the UKIP ‘earthquake’.

Northern Ireland

I won’t pretend to have anything resembling an adequate knowledge of Northern Irish politics (I don’t think any outsiders truly understand what goes on over there!) so I’ll just make up a pretty table and give some basic observations.

There don’t seem to be many big changes here. Sinn Féin and the DUP have both reasserted themselves as the major parties of Irish republicanism and unionism respectively, at the expense of the UUP and the SDLP. UKIP have failed to make particular inroads into Northern Ireland, presumably because there’s not the gap in political nationalism it’s managing to fill in much of England and Wales. The overall nationalist vote was 38.5% (-3.7), the unionist vote 50.9% (+1.9) and the ‘other’ vote 10.5% (+1.7). The unionists achieved a majority, though the politically neutral parties have also managed to make gains. Given demographic trends I doubt the population is becoming more unionist in ideology, so I suspect any other trends are quirks of turnout and represent no real change in political feeling within Northern Ireland. Once again, the problem of seat distribution is raised, given that unionist parties took 67% of the seats compared to just 33% for the nationalists, but I also can’t think of what would be an easy solution to this.

United Kingdom (excluding Northern Ireland)

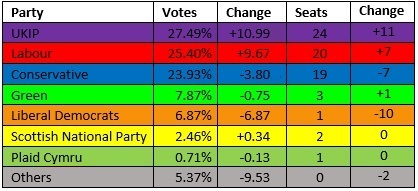

Watching region after region declare spectacular gains and victories for UKIP would either have been an exhilarating or thoroughly depressing experience depending on your perspective. There is no doubt that UKIP won the election, this being the first time neither Labour or the Conservatives won the most votes in a national election since 1910.

In some ways, these results aren’t particularly surprising. Both the coalition parties took the standard ‘anti-government’ hit to their vote, with the Liberal Democrats bearing the overwhelming brunt of this as usual. The official opposition, Labour, picked up a strong anti-government vote. UKIP soared ahead as polls predicted. Yet it’s being portrayed by the media as a UKIP landslide, labelling every single other party’s performance as a defeat. This isn’t entire untrue; as previously mentioned, this is the worst result for the major parties in a century, achieving less than half of all votes between them (though, despite the media narrative, their combined share actually increased by over 6 percentage points). This is an unprecedented result for UKIP and leaves them in very strong stead for the general election. The Liberal Democrats have been wiped out, barely clinging onto 1 MEP of 11; Nick Clegg’s position as party leader appeared tenuous at best the following morning and, while he seems to have partially secured his position since, there continues to be dissent within the party over the viability of his leadership. Despite a strong improvement on their 2009 result Labour had hoped to do much better, beaten into second place and only slightly above the Tories. This prompted panicking among Labour commentators and, I’m afraid, has increased pressure for the party to take an even harsher line on immigration in a foolish bid to ‘out-UKIP UKIP.’ The Greens will welcome their extra seat, and enjoy the prestige which comes of having triple the number of MEPs as the Liberal Democrats, but the drop is national vote share will surely be a disappointment. Despite losing votes, David Cameron seems to be in the best position of all major party leaders. If he can count on much of the UKIP vote returning to the Conservatives next year, this result indicates the party has a decent run at winning next year’s general election.

The parties will respond to this in different ways. The Greens and the Liberal Democrats, assuming the latter doesn’t suffer a coup in the next year, will probably stick to their pro-EU, pro-immigration messages, and rightfully so. The Conservatives have already made attempts to placate UKIP voters by offering an in-out referendum which, despite apparently failing to stem the rise of UKIP, will probably be the route they continue down. Labour, in contrast, appears poised to take a much more UKIPesque line on various issues. In the last couple of decades Labour seems to have become a party intent upon chasing the centre-ground rather than leading public opinion, and if it assesses that anti-immigration feeling is the current centre-ground I would fully expect the party to adopt such policies. This would be a mistake. I know you’re not supposed to agree with Tony Blair these days but he hit the nail on the head when arguing Labour should confront UKIP, not pander to it (while also correctly diagnosing the Lib Dems’ problems as being unrelated to their stance on Europe but instead a result of their lurch to the right within the coalition, something Labour strategists seem to have forgotten).

Here’s why. Across the UK, 43% of voters supported pro-EU parties (55% when the Conservatives are split) compared to the 31% which is avowedly anti-EU (44% once the Conservatives are split). Opinion seems to be divided in half across the country, though the pro-EU vote still has an edge over the Eurosceptics. It is not true that a vast majority of the British public support withdrawal, and Labour should realise this. Rather than join the side of the Eurosceptics, Labour should seek to dominate the pro-EU ground. If it doesn’t, it should expect to see much more of its vote slip away to parties which do offer a counter to UKIP’s policies – most likely to the Greens. Over half of the UKIP vote came from former Tories, compared to just 20% from Labour; it would be foolish to seek votes from a group whose natural persuasion is not Labour. Furthermore, this result cannot claim to be a fair representation of opinion in the UK with merely 34.19% turning out to vote – only just over half of the people who tend to vote in general elections. Chances are, the majority of people who have strong anti-Europe, anti-immigration views would have turned out to vote for UKIP, but there’s still that whole 75% of voters who didn’t feel strongly enough to vote at all. This is the group Labour should be targeting. No matter how hard they try, they’ll never be able to take a stronger line on Europe and immigration than UKIP, but they can appeal to the majority of people who currently see no purpose in voting.

There is no doubt that the European Parliament has proved to be an anti-establishment vote in the UK, but that’s evident more from the dismal turnout than UKIP’s electoral gains.

European Parliament

It disappoints me that the greater picture of the European Parliament election hasn’t been adequately represented in British media. The mainstream media, especially the BBC, have been intent on painting it as a great revolt against the EU, pointing to examples of countries which had a strong rise of anti-establishment parties such as the Front National in France and Syriza in Greece. We hear less of Germany, where the ruling Christian Democratic Union dominated the election and kept the only significant Eurosceptic party down at 7%, or of Sweden where the Social Democrats and Greens, both pro-European, together came close to taking a majority of the seats. Nor do we hear about the success of Europhile parties in eastern Europe, where attitudes towards the EU tend to be much more positive. Here’s the overall result of the European Parliament election:

Majority = 376 seats.

It’s impossible to deny that there has been a shift away from the four major pro-European parties, collectively losing 89 seats. Many of these seats have gone to parties like UKIP and the National Front, though it’s worth pointing out that the group UKIP sits in only gained 7 seats (which is much less of an ‘earthquake’ than much of the media would have you believe). This anti-establishment backlash has most greatly harmed the EPP and, to a lesser extent, the Liberals; the Socialists and Greens have more or less held their ground. Although the EU will undoubtedly come under pressure from national leaders who faced domestic defeats, including David Cameron and Francois Hollande, it must be acknowledged that 69% of the European electorate voted for parties in groups with a positive attitude to the EU. Yes, this is down from 80% in 2009, but given the scale of Europe’s successive economic crises in the last five years it’s remarkable the drop wasn’t greater. The European people have not voted against the EU.

Therefore, the EU mustn’t let Eurosceptic national leaders seek to portray this result as a mandate for unravelling the European project. This is already happening with the debate around who will be the next President of the European Commission (effectively, the European Commission). A candidate for this position must be nominated by the Council of Europe, which comprises the 28 heads of government across the EU states, which must then be approved by the European Parliament. As of the 2009 Lisbon Treaty the Council of Europe have been instructed to take into account the democratic will of the people, as represented by the elections to Parliament, in selecting their nomination. It is unclear exactly what this means, but as each political group selects their own candidate to be the new President (unless they decide to be awkward) I think the assumption is that the group with the most votes ought to have its candidate be elected. In this case, then, the next President should be the EPP’s Jean-Clause Juncker. However I see David Cameron already seeking to prevent him from achieving the Council’s nomination on the grounds that his policies are too supportive of greater expansion for the EU. I believe Francois Hollande has taken a similar position. The collective leadership of the Council should not acquiesce to these leaders reeling from their own domestic humiliations when the democratic will of the European people is for a pro-European President, of which Juncker received the greatest mandate.

————-

Okay, reaching 3,000 words is usually a good place to stop. I’ll finish with another disclaimer that I’m not an expert on anything I’ve written about; these are simply my responses to both the election result and the way it’s been portrayed in the media.

Pingback: 2014 England Local Elections Result | Through The Fringe

I have sent a link to this to my wife, who is into politics.

Thank you!